Wading upstream through cars and hawkers, past shops glowing with ornate 24 karat bling, we decided to take a risk on an unassuming little restaurant. Our table was just off the sidewalk, open to the Kuala Lumpur night in Little India. After amazing dosas and delicious Indian treats, for the first time, I tried chai masala tea and I fell in love with its spicy creamy warmth. It’s been over a decade, and I still remember my surprise and delight at being wrong.

Wading upstream through cars and hawkers, past shops glowing with ornate 24 karat bling, we decided to take a risk on an unassuming little restaurant. Our table was just off the sidewalk, open to the Kuala Lumpur night in Little India. After amazing dosas and delicious Indian treats, for the first time, I tried chai masala tea and I fell in love with its spicy creamy warmth. It’s been over a decade, and I still remember my surprise and delight at being wrong.

Years before that, my brother told me that chai is great & tried to get me to try it; I rejected it without even a taste. I “knew,” beyond a shred of doubt, that chai was bad. I’d never tried it, heck, if I’m honest, I’d admit I didn’t even know what it was! But I was certain and a bit superior in my confidence, and I had that sense of digging my heels into the ground, ready to battle to be right.

Yet in the steamy evening air of KL, it was so easy to try something new. Why?

Why was I so happy being certain… and then why was I completely open to the risk later? In addition to being a bit of a self-righteous idiot, it turns out that there is an important set of neurological functions at play here. A brain battle that has important implications both personally and organizationally.

Safety vs Learning: The Neuroscience Trap

A sophisticated brain is the human edge — they allow us to negotiate the risks of a complex world — to survive and, hopefully, thrive. To do that, our brains need a quick way of testing: “Is everything ok?” “Are we safe?” One of the most basic “acid tests” our brains use is comfort: When we’re comfortable, our brains surmise, all is good.

This is a paradox and trap, because in a rapidly changing environment, short-term comfort often has deleterious consequence. The “comfort test” works better when life is very stable; it prevents us from falling into difficult unknows and going off the deep end. But since innovation and growth require some risk, some departure from the comfort zone, the “comfort test” has a terrible cost. To balance this pressure toward sameness, our brains also have the capacity to project, to imagine, to plan for the unknown — to go into new territory without having to actually having to face the dangers.

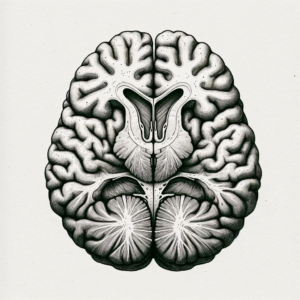

Zooming into the neurobiology, in a sense we have a tug-of-war between the striatum and the amygdala, between opportunity and risk. The striatum is part of the basal ganglia, a “bump” at the lower-back of the brain implicated in many aspects of decision-making as well as balance and navigation. Interestingly, this center seems to manage balance both in terms of physical motion and in terms of wisdom. The striatum, specifically, is tied to reward, novelty, and forward planning. When we’re looking ahead, anticipating with pleasure, and innovating the striatum is active.

Zooming into the neurobiology, in a sense we have a tug-of-war between the striatum and the amygdala, between opportunity and risk. The striatum is part of the basal ganglia, a “bump” at the lower-back of the brain implicated in many aspects of decision-making as well as balance and navigation. Interestingly, this center seems to manage balance both in terms of physical motion and in terms of wisdom. The striatum, specifically, is tied to reward, novelty, and forward planning. When we’re looking ahead, anticipating with pleasure, and innovating the striatum is active.

However, when we’re anxious or uncertain, activity here decreases. For example, a team of neuroeconomists at Caltech ran an experiment with decision-making; as uncertainty increased, fear centers in the brain became more active while there was decreased activities in the striatum (Ming Hsu et al 2005).

As doubts creep in, activity in the amygdala increases and we move more into a fear/reaction/protection response automatically rejecting the novelty. As the incisive Jonah Lehrer puts is, “This the curse of uncertainty: it makes everything feel unappealing” (2010). Conversely, of course, we experience the blessing of certainty: It makes everything feel better. We “know the answer” and don’t need to deal with the doubts… very comfortable! But we don’t learn.

Since learning is so important to human survival, we have also developed wiring to motivate learning, but this will be regulated by the comfort/risk dynamic. Dopamine, a neuro-chemical that gives us a kind of internal reward, is often associated with pleasure-seeking. In a fascinating meta-analysis of brain imagery studies, Roy Wise found a connection between dopamine reward and “stamp in” a useful response, which, he says, is “ essential for the control of motivated behaviour by past experience” (Wise, 2004) — aka, learning. When we plan ahead, consider possibilities, try something and experience success, we get this lovely reward of a rush of feel-good-dopamine.

Learning to Take Risks

So why was it easier for me to try chai in KL? I suspect there were two factors, each with significant implications for individual and organizational change.

One – in a situation where I was actively learning, awake, engaged, exploring, the dopamine-learning-reward pathway was already highly activated. So my brain was telling me, “learning feels good!”

How can we activate that positive experience of learning for ourselves and others? If we do, it will open people to new learning.

Two – I was out of my usual context, so it was normal to be uncertain, but I was not so far out of my comfort zone as to shift over to protection.

How can we get ourselves and others out of our usual context, into a situation different-but-positive enough that new perspectives create curiosity rather than righteous ego-protection? If we do, it becomes less important to be certain because we’re on an adventure.

Do you see ways of strengthening these two conditions in your life, in your classroom, workplace team, or organization? If innovation, growth, and learning are key for you to reach your goals, then ensure these two drivers are central to your planning and I suspect you’ll find the process faster and more efficient — not to mention a whole lot more fun.

At a personal level, I see this dynamic recurring in many places. I am “sure” and happy in my rightness, and I use that excuse to evade. Perhaps the most destructive version is that I spent decades evading exercise because I was sure that it wasn’t good. Now that I’ve given it a shot, I’ve come to discover that all those people who said, “once you get into it, you’ll love it,” were right. Yet even now, I feel this resistance to admitting that I was completely wrong. It’s like being “wrong” is very bad, very dangerous — subconsciously “wrong” means I’m not trying hard enough, it means I’m not worthy of recognition. Yet I am absolutely certain that uncertainty, balancing in a place of risk, being willing to stay in discomfort, is the most powerful step toward real growth.

—

For more on this topic, see Coaching Like a Vacation: 3 Emotional Intelligence Tips to Make Change Work Better 🌱

—

This first version of this article was published on staging.6seconds.org Jan 31, 2011. Updated January 15, 2024.

- Coaching Through the Emotional Recession: Three Practical Tips for Trauma-Informed Coaching - May 1, 2024

- Knowing Isn’t Coaching: Three Emotional Intelligence Tools for Professional Coaches - April 3, 2024

- Coaching Down the Escalator: 3 Emotional Intelligence Tips forCoaches to Reduce Volatility & De-escalate Conflict in a Polarized World - March 6, 2024

Everytime I read you, I receive the present of reflect and motivate myself to do better.

In our spirit of Change is now natural to thing How to Activate this reflection.

An article with date 2011 is so actual in 2019.

Hoping to see you soon in April in Italy , I say Thank to you and all network for the power of this ispiration .

I ‘m sure that when we are in a learning process everything here in http://www.eq.org could help us to be active part of that billion of people.

You writing style is remarkably effective (at least for me). The story sets the context and how you blended that with neuroscience made it a cakewalk read. I am definitely sharing this experience in my learning programs when I talk about Fear as an emotion and what happens during uncertainty. Thanks Joshua.

Thank you John!

🙂

Josh, great to see that you have learned to love exercise. That way you’ll be around to share pearls of wisdom like this one for a long time.

I found this article in the field of neuroscience very interesting. “… our brains also have the capacity to project, to imagine, to plan for the unknown — to go into new territory without having to actually having to face the dangers” This idea that we can plan ahead, tactically and strategically, when we know how to do it, helps us to imagine lots of different scenarios. So this is how we can learn to be creative?

Hi Josh. As I read this article, I remember that as a child I would be first in the line for vaccinations in school, or having my decayed tooth removed, or to volunteer for things to be done, etc. As an adult, I have this “daring” to try something new, or to do something I haven’t done before. I remember in college, I was among the few students to wear fish nets and colored stockings. And yet I turned out to be a balanced individual. I have read several articles written here on the self-science curriculum and it would be very interesting to explore the areas and opportunities where we can teach children to balance daring and caution or have practical tools we can learn to help parents impart this “skill” to their children.

Josh, your blog posts are always so valuable. Thank you for the many contributions you make to our emotional intelligence awareness. I love Chai, perhaps it has a few magical properties of its own that added to your experience?

I will use this story in my seminars, with credit to you of course. Please keep sharing!

Joshua,

I couldn’t agree with you more….. being willing to remain in a place of uncertainty is essential to learning, though it can feel so vulnerable initially. Following are a couple of my favorite quotes relating to this:

“Until you are willing to be confused about what you already know, what you know will never become wider, bigger or deeper.”

Milton Erikson

“Life isn’t about how you

survive the storm, but how you dance in the rain”

Thanks for the reminder!

Jan

Awesome Josh. Stories like this help us learn the complex lessons of our brains and emotions. I’m also reminded that our intelligence is behind our tendencies to worry. If we’re wired to look for disasters in the future. and if our protective brain seeks to avert problems by scanning the environment for them–does more analytical intelligence = more worrying?

It is further interesting to note that the Basil Ganglia is also implicated in excessive worry and avoidance conflict (at any cost). I often work with young people with brain impairments, specifically Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders, where it is KNOWN that the BG is one of the areas with impariment. Often LEARNING is the biggest area of difficulty, and going from the specific to the general nearly impossible!

When looking at SPECT scans of people with many anxieties, the BG is highly active. Daniel C. Amen, in his great book “Change Your Brain, Change Your Life” talks about this at length.

Sometimes knowing that it is a part of your brain that is running hot… and can be calmed… is relieveing to people (and kids) who love to do fun things to “boost the brain!” Instead of calling it “the worry wart”, looking at it through a neuroscience lens allows it to be in the realm of possibility.

Another thought… looking at culture shock and the way different groups respond to host culture demands can put it into the realm of “group learned” behavior also. Our brains are wired by experience, and culture plays a huge role, I think, in determining tendancy.

I am so glad you have found CHAI!!! It must be REALLY dslicious in KL.. I have had it in India from the street vendors… YUM

martha white

Hello Josh, welcome to the blog-o-sphere. I’ve been blogging for about a year at http://www.blatner.com/adam/blog/

Your reflections are good. I’ve been interested in the power of illusion, and it has neuro-physiological correlates, too. Many psychologists are exploring varieties of self-deception and writing books and papers—and all this is well beyond Freud, but resonates positively with some of his ideas. I’m not talking about many of Freud’s more specific concepts, but the general spirit of recognizing the deep power of self-deception—or what in Yoga and Buddhism is called Maya, the power of illusion, personified as a goddess.

Your recognition of the value of self-questioning and creative self-management as a modest counter to this tendency is good—I may even review and reflect on it.

By the way, the website has nice black letters, but the email is in a light black or gray, quite difficult to read. What’s that about?

I’m the psychiatrist, bald with glasses and beard, met you in 2000 and 2002 at your conferences, very allied to your intent to get psychological literacy (what i call it) out there in the world.

Warmly, Adam

Dear Joshua.

In fact, all your reflexions here, take me to the coaching area.

I feel to much EQ in the coaching field than no other, cause as you know we need to have so much “know my self” and empathic attitude to go fw in the learning path for our coachees.

I remember all the time when I work with my coachees in several things going from EQ and we work together.

So, coaching and emotional intelligence work together and it can’t be split. We need all the EQ tools to became a good Coach.

I intend to speak about this in my next conference in the 40 world of IFTDO congress in Poland next May.

Thank you Josh and Best regards

Manu

Thanks Manu – great to hear from you again. I absolutely agree w you – in our SEI Coach Training, which is a program for coaches to use Six Seconds tools in coaching – we emphasize a parallel process: As you Know, Choose, Give Yourself as a coach, you, in turn, engage your client in this same discussion of awareness, choice, and purpose.

Warmly,

– Josh