What does it mean to feel, and why does it happen? When we look at emotions as “good” or “bad” we’re in a constant state of internal struggle against our own emotions. Is there another option? How can we shift away from this dualistic view and make friends with ALL our feelings? This article includes Josh’s feeling list (explained at the end of the article) you can access with the button:

by Joshua Freedman

Imagine the “archetypal” child and parent, let’s take a boy, about eight years old. His parent is busy dealing with 3.3 million tasks and chores, it’s been a long day and everyone’s on thin ice. The child is going about the business of childhood and something happens – almost irrelevant what it is, and he gets upset — it’s been a long day for him too. Let’s suppose he’s highly upset, unreasonably upset, and acts that out: he slams something down, he kicks something, he shouts, and overwhelmed by this rush of feelings (and afraid of his parent’s reaction) he starts to cry.

What is the parent’s typical reaction? Frequently it translates to “stop” – sending a clear message of invalidating the child’s feelings. Most of us have grown up with those messages, and we’ve learned: “Some of our emotions are bad” – but what if that’s wrong?

Dismissing Feelings

In your own experience with emotion, what did you learn? What’s the story you heard about feelings like anger, fear, hurt, or jealousy?

I’ve been privileged to work with people from over 100 countries, and around the world, people have told me much the same thing: Those are “negative” feelings. Even “bad” feelings. We find them uncomfortable, overwhelming, scary, out-of-control (and now we’re having “bad feelings” about our “bad feelings”).

So, what is the natural, reasonable, response to something bad? Control it. Push it away. Cover it over. Squish it. Or at the very least, hide it. Maybe after some therapy, “manage” it. As Marge Simpson said to Lisa: “Push the bad feeling down down down ’till you’re standing on it, and smile.”

What about embracing these difficult feelings?

Increasingly people are happy to do that with “positive” emotions – the happiness-fad seems to be slowly waning, but there is still a pervasive message: Happiness is good, so if you’re not happy, there’s something wrong. This attitude is fraught with judgment; we’re limiting the motivating power of feelings to a select few. We’re deciding that some emotions are good… which requires that others are bad.

In the last 24 years of teaching about emotions as a driver for positive change, I’ve come to consider that this vilification of our own emotions is the single biggest obstacle to emotional intelligence.

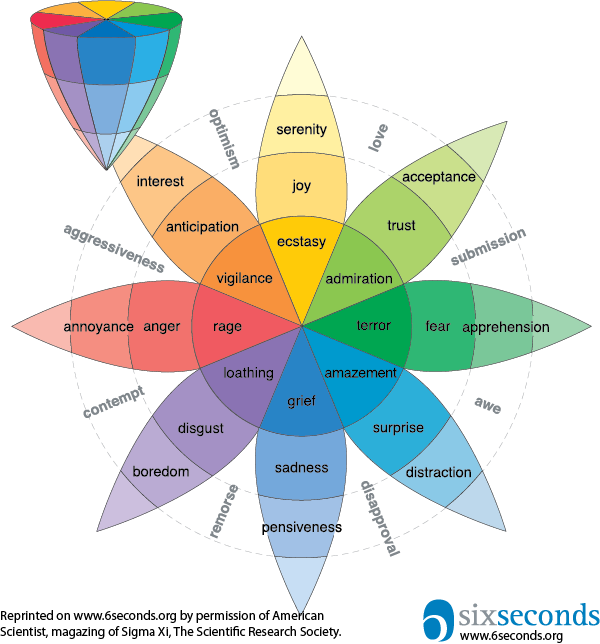

Going Deeper with Pluchik’s Wheel of Emotions

The Plutchik Model offers a beautiful framework for exploring the meaning of emotion. I’ll explain the model and the value of it — and then the fatal flaw of dualistic thinking. Then we’ll look for another view.

If you’ve not explored our interactive version of the Plutchik Model, it will give you insight on why this feeliings wheel is so useful, but below I’ll go in more depth about the meanings and the limitations.

What’s Useful in Plutchik’s Wheel of Emotions

Robert Plutchik was a psychologist who became interested in the way animals (including humans) use emotions to help aid survival. Following in Darwin’s tradition, that there is an adaptive purpose to emotion. In other words: Feelings help animals survive by alerting us to threats and opportunities, and by providing a universal, cross-species communication mechanism. If you’ve ever heard the angry snarl of a wolf, or been enchanted by a puppy’s playful grin, you’ll understand this viscerally.

Plutchik proposed a model of eight basic emotions that he organized in the 3D “ice cream cone” model shown on the upper-left of the wheel. He placed them in opposite pairs based on the physiological response each provokes. For example:

An angry dog gets big, loud, and move towards a threat.

A scared dog gets small, quiet, and moves away from threat.

Most emotions researchers organize feelings in other ways, eg putting fear and anger side-by-side because we often experience them together… but remember Plutchik was looking at physiological responses:

| Emotion + physiological response | Opposite emotion with opposite response |

| Anger → Attack | Fear → Protect |

| Disgust → Reject | Trust → Embrace |

| Sorrow → Close | Joy → Open |

| Surprise → Look Back | Anticipation → Look Ahead |

Emotions Are Signals: Understanding the Meaning of Emotions

There are many different ways of defining emotions (and here’s an explanation of emotions vs feelings vs moods). Researchers in this “adaptive” tradition define emotions as basic physiological responses to help us survive and thrive where emotion (a) focuses our attention to a threat or opportunity, and (b) motivates a response.

Anger, for example, is a signal that our pathway is blocked. We want to be promoted, we perceive someone is interfering with that, we are angry at the person. The anger serves to focus our attention on the threat and motivates a response of fighting or pushing through the obstacle.

Here is a chart of the eight basic emotions and a likely description of the focus and motivation provided:

| Basic Emotion | Focus | Motivation |

| Anger | Problem | Fight or push through |

| Anticipation | Opportunity | Move toward |

| Joy | Opportunity | Do more of this |

| Trust | Safety | Connect with others |

| Fear | Threat | Protect |

| Surprise | Uncertainty | Stop and look |

| Sadness | Loss | Stop and clarify |

| Disgust | Problem | Reject |

The Good & Bad of Thinking of Emotions as Opposites

We can use this table to “decode” our emotional experiences. It shows us that emotions serve a purpose, that there is value in all feelings.

Unfortunately, even though Plutchik came from an adaptive tradition (all emotions have value), in this model it’s still easy to say that some are “negative” because they’re tied to problems or threats.

This judgment of some feelings as negative leads people to use strategies such as emotional suppression. What’s wrong with suppression? In some cases, it’s helpful, but as a long-term coping mechanism, it’s not. For example, this study shows suppression reduces about ability to think clearly, this one shows it contributes to increased intensity and psychological distress. There’s also a concern, as explored in this study, that suppressing “negative” feelings also reduces happiness.

One of the main challenges I see is that when we’re judging some feelings as negative, and we feel those, then there is something wrong with us.

I remember talking to a coaching client who’d heard me explain this, and she said, “I know that there are no negative feelings, but I have a problem with anger.” When I asked her to explain more, in essence her conclusion was, “Anger is bad, and since I feel angry, I’m bad.” Try as I might, we couldn’t get past this obstacle because her cultural norms around feelings (and particularly gendered feelings which I explain in this video) were so deeply entrenched.

Can We Use Less Negative Judgments to Describe Problem-Related Feelings?

We can try to remove the judgment and call some of these “pleasant” or “unpleasant” to reduce the negativity bias. That doesn’t quite work because so-called unpleasant feelings are often not unpleasant. For example, sometimes when I think my son is defying me, it feels very pleasant to express my anger. Conversely, when my dad died, it felt right (not exactly pleasant, but good-hard) to feel sad.

Another approach is to characterize them as “contracting” versus “expanding.” It is useful to consider that feelings tied to problems narrow our attention and cause use to zero-in on the issues, to slow us down, to restrict our risks. At the other end, some feelings energize us to look outward, to become more open, and to take risks. Of all the “polar” characterizations this is my preference because it’s genuinely non-judgmental.

However, I’d like to go a step further. How could we step out of the “negative emotions” trap and find a way of characterizing emotions without judgment?

In Buddhism, and many other faith traditions, there is a notion of “non-duality.” Rather than good and bad as opposites, they can be seen as one, a whole with balancing sides. This is visually represented in the yin-yang symbol. In that graphic, the universe (a circle) is half and half… but not actually divided. The black and white are interlocked – they are one circle with two aspects.

Is there a way to think of emotions as neutral data … as messages from us, to us, about what matters?

Is there a non-dualistic view that values all emotions?

Rather than characterizing feelings as opposites (good/bad, pleasant/unpleasant, contracting/expanding), is there a way to see them as a linked whole? Often people in my work describe emotions on a continuum – a spectrum from one extreme to another, taking an emotion and it’s opposite as ends of the number line. This has some merit because we’re starting to link them as part of a whole, but it’s still dualistic: There are positive and negative integers on the number line.

Anger as part of Motivation

To find a different way of thinking, let’s go back to the definition of anger from the Plutchik Model: You feel angry when you want to go someplace, but your way is blocked.

So anger arises from that combination of “desire to move” and “obstacle in the way.” In other words, we could say that there is actually no such thing as anger without commitment: If you don’t want to go anywhere, you won’t get angry! In other words, they are not two separate things: Anger only exists in contrast, in balance, in context of commitment.

What, then, could we call that feeling of “wanting to go someplace”? Perhaps anticipation? Or maybe commitment is a more powerful version of that word?

Fear as a signal of Priorities

How about fear? Fear is a message of potential threat – a signal that something you care about is at risk… so if you don’t care, you won’t feel fear. In other words, fear and caring (aka love) are also a non-duality.

Sorrow as a message of Significance

Sorrow arises when you are losing someone or something that matters – a meaningful relationship, a significant person. But when we feel that sense of meaning and significance, we experience it as joy.

Disgust as a part of Safety

Finally, disgust is a signal of violation. It means rules are broken, agreements at risk, the systems and structures of relationship are in peril. Yet if we did not feel trust in those very same things, if they did not signal a sense of safety and balance, then we wouldn’t care if they were imperiled.

Are they really opposites?

At this point, I’m fairly content with a hypothesis of these constructs – not as opposites, but as wholes. The dark and the light of the candle, but there’s still something missing.

I’ve been thinking about this problem for several years, and recently I heard an idea that I’d like to consider. I was privileged to be on a panel with Dan Shapiro, a professor at Harvard Law & Medical Schools, and the co-author of Beyond Reason: Using Emotions as You Negotiate. The conference was on emotional and spiritual intelligence in negotiation at Harvard Law School.

In describing the challenge of first identifying – and then actually dealing with emotions in the complex dance of negotiation, Dan’s succinct summary: “It’s really tough!” So his proposal is to notice emotion, but to go to a deeper question: What’s the basic need driving the emotion? Since there are a relatively small number of basic needs, perhaps five, it may be easier to handle this set. If we can attend to these five basic needs, Shapiro’s compelling case is that it’s far more likely that a true negotiation will arise.

Grappling with Emotions Can Be Really Tough!

In all this abstract thought about feeling, it’s also to remember the visceral power. Emotions can be BIG and confusing. It’s easy to feel overwhelmed or lost in the emotions. Yet what if… maybe… those are the times of greatest insight?

Typically when talking about basic needs, the premise is that a whole range of emotions will surface in response to a need being met or not met. In Nonviolent Communication, Marshall Rosenberg and colleagues have done wonderful work illustrating these dynamics; the problem is that’s a dualistic model – again, is sorrow inherently about an unmet need? Or is sorrow sometimes present because we have loved so deeply?

Hearing Shapiro use basic needs as a way of explaining the emotional dynamics of negotiation, I wondered if we could look at the “emotional non-dualities” through this lens. But rather than being in the duality of met/unmet needs… what if emotions are all signals of something important?

What if feelings tell us: Something important is happening?

With this principle, I began to consider emotions in a new way: Instead of thinking of emotions as opposites, what if they are ALL simply signals of something important?

Here are some examples:

Anger or Commitment are tied to wanting to move, a need to achieve. It’s pretty easy to see that this emotion-pair arises in conjunction with a basic need that could be called accomplishment.

When we feel Disgust or Trust, it means the social contract that produces order is vulnerable (this contract can be within ourselves, and when we violate our own precepts we feel disgust turned inward). While fear also signals risk, it’s not usually tied to the contract but to the human implication. And it’s trust that signals safety; so perhaps the specific surety of trust balances with a specific peril of disgust, in which case this construct is tied to the basic need of safety.

While Fear and Love can arise a connection with an inanimate object (fear of losing a home), I suspect this dynamic most deeply rooted in a desire to nourish others, to be in a balance or harmony. To be connected. This could be called the need for belonging.

Again, the Sorrow-Joy dynamic seems to arise in a range of situations, but I’ve been thinking about the biology of joy. Joy is produced by opiates that are absorbed in many parts of the brain, but especially in the frontal cortex, the seat of evaluation. This is an intriguing pairing because it implies that somehow when we truly understand, we’ll get the reward of inner bliss. We could call that pursuit of meaning the need for purpose.

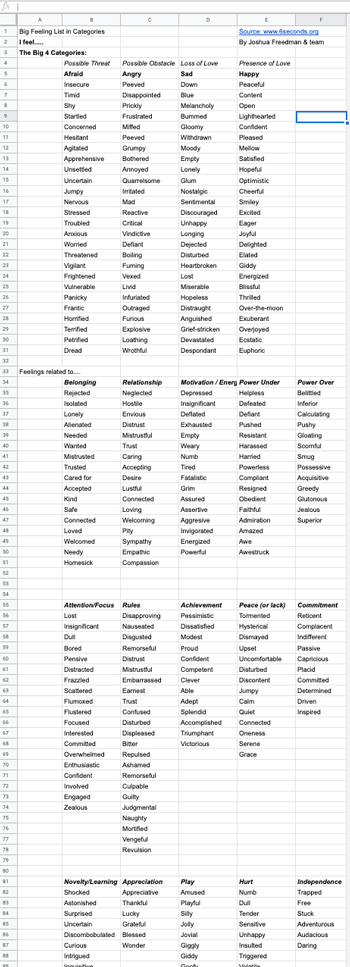

I’m continuing to work on this approach, and have identified several feelings in this logic of “big messages”; more are below, plus, you are welcome to access my google sheet where I’ve categorized several hundred common feelings:

Download Josh's Big Feelings List

I’ve been working on a list of feelings in categories based on this logic of emotions as signals of what’s important. You are invited to access the list to use it for your own learning… And, if you’d like, please add comments / suggestions to help it grow.

Unlocking Emotions

In Six Seconds’ Unlocking EQ course, we developed this model further using the metaphor of emotions as keys – with tags printed with pairs of feelings on obverse sides.

In Six Seconds’ Unlocking EQ course, we developed this model further using the metaphor of emotions as keys – with tags printed with pairs of feelings on obverse sides.

One pair that personally find challenging is Lonely & Included. I think it’s because I often felt isolated, and I did not know what this meant, I came to see loneliness as something negative. But what if, for all those years, loneliness was an invitation? What if feeling lonely and included are not opposites — what if they’re both messages about what matters to me?

One of the other pairs, shown to the right, is Hope & Despair. It’s awfully difficult to not see despair as negative – such a heartwrenching experience… and in the midst of despair, hope seems like it will never come again. Yet when we’re in the midst of despair, we do care deeply. We’re not apathetic. We’re grieving the might-have-been. This is a time for the work, the exercise, of optimism. And it’s in this state where come to understand the real opportunities in life, and our role, our agency, within the pursuit of what’s possible.

For all these challenging feelings, the key to this shift, for me, is to stop resisting. To say: This feeling matters. It’s here to help me. It’s a message about what I’m perceiving to be truly important. Something that helps me is this quote from Seneca:

Three Key Messages To Remember About Emotions

It’s likely that in our day-to-day lives, there are more basic needs than these, and certainly many, many “wants.” The needs and wants are tied to a big range of feelings. But perhaps if we can distill this down to a simple level, the complexity of our feelings becomes easier to understand – and to manage. While I’m uncertain if these labels are wholly adequate, there are three key messages that I hope you’ll take away:

1. Emotions are signals that are here for a reason.

They should not be “blindly obeyed,” but nor should they be ignored.

2. Emotions are about what’s important (that you’re perceiving)

There is an innate connection between needs and emotions. In trying to make sense of your own or another’s feelings, consider that they might be signals about a core need.

3. Emotions are neutral – data and energy

Although feelings can be uncomfortable and overwhelming, resist the urge to judge them – and to judge yourself and others for having them. Instead, consider that each feeling is part of a larger story, a story of what’s truly most important.

Thank you to Ayman Sawaf for sharing Lazarus’ work and explaining that emotions come in pairs, to David Caruso for teaching me about the adaptive value of feelings, and to Dan Shapiro for the thinking about needs.

What's new in emotional intelligence?

Emotional Intelligence at Work: The Free, Easy Win Most Managers Are Missing

Gallup study compares the biggest gaps in employee vs. manager perceptions. What are managers’ worst blind spots? What are easy wins they could do better to improve team performance?

Effective Emotional Intelligence Coaching: 4 Questions to Improve Client Outcomes with Social and Cultural Insights on Emotions

Improve your emotional intelligence coaching by understanding the social and cultural influences on emotions. Ask these 4 key questions for more effective client relationships

Krish and Anabel: SEL Pioneer and Mentee Share 6 Life Lessons on Empathy, Integrity, and Emotional Intelligence

What are 6 life lessons you’ve learned? Dr. Anabel Jensen, SEL pioneer and Six Seconds President, explores this important question with her 16-year-old mentee.

Voices from the Network: Jeremy Jensen

In this Voices from the Network, we sit down with Police Chief Jeremy Jensen, who is doing emotional intelligence training with his officers in Dubuque, Iowa.

Emotional Intelligence at Work: Is There Hope for Toxic Workplaces?

The remarkable transformation at Westcomm Pump offers a blueprint for turning around workplaces with depleted morale and trust issues, using the Team Vital Signs assessment.

Coaching Through the Emotional Recession: Three Practical Tips for Trauma-Informed Coaching

World Health Organization Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in March 2021, “When there is mass trauma, it affects communities for many years to come.” While coaching isn’t a “treatment” for trauma, in the Emotional Recession we’re facing now, chances are, your clients, colleagues, and you are carrying more trauma than 4 years ago. What do we do as coaches?

- Coaching Through the Emotional Recession: Three Practical Tips for Trauma-Informed Coaching - May 1, 2024

- Knowing Isn’t Coaching: Three Emotional Intelligence Tools for Professional Coaches - April 3, 2024

- Coaching Down the Escalator: 3 Emotional Intelligence Tips forCoaches to Reduce Volatility & De-escalate Conflict in a Polarized World - March 6, 2024

Needs Maslow. Anger Aristotle

There is a link to Josh’s Big Feelings List but it doesn’t lead to anything. Is there another way to access this list?

Thank you Joshua for an inspiring article. I am new to the Emotional Intelligence tribe and era, and I would say going through this article made me reflect on how intelligent is “Emotional Intelligence” in gearing the reader/end-user/client to adapt emotional intelligence strategies in his/her being. I have fully resonated with good and bad, black and white, opposite feelings are not really opposite, they are like yin and yang (non-dualism) and they complete a circle not a line with two ends, mirroring each other and they exist for reason. Therefore, when we encounter an undesired feeling, let’s not suppress it, ignore it or exaggerate with it, actually, its there for a reason, and knowing the reason is a virtue to enable us to move forward. In today’s world, we tend to fall in the norm of “think positive”, “stay around positive people”, stay around happy people” etc… I do agree that its healthy and contagious being surrounded by positivity and happy people and the environment. But, on the other hand, if we have a visitor named “sadness”, “anger”, loneliness” etc.. let’s welcome it and have a chat with it, get the information of what is it we need to know, make it a short visit and scale forward. thinking outside the runner and having an open awareness thinking pattern is what I have perceived from the Harvard Summit notes on Emotional Intelligence where “let’s negotiate third option kind of”. The Plutchick model is a resourceful tool and seems possibilities are endless with how to make use of it. Finally, when someone is stressed, in a state of being angry, upset, betrayed, etc.. most likely that person is not in a state of being resourceful and reflects clearly on whats the message he/she is to get from this. I personally, allow the feeling, use some techniques to prevent being in that state for long such as (counting till 6 (6s), take deep breaths, change my physiology, change the picture I make in my head to be able to change the feelings towards it, meditate is possible, and more ) . I do see the emotional intelligence field is a very grounded one, supportive to human beings, and it is a life long journey. I am personally planning to dive more into this field of science aiming to serve others as well. Thank you again

I like the idea of welcoming emotions and having a chat 🙂

Thank you for this wonderful article. I experienced it as very nourishing. Step by step my understanding of emotions and how to appreciate awareness of feelings and connection with others is calming my nervous system and opening my heart. It is a process of discovery that will last a life time, an interesting Koan that replaces the striving for some other experience or image of accomplishment and allows the mind to relax in the body and be content in the here and now.

I liked this article! I like the Plutchick illustration, although I do have some ideas that differ with the concepts shared. One is the idea of a continuum, and I look at that through the lens of stress and trauma. In the stress response (automatically a threat response), there is a narrowing of emotion, and I think that along with the neurophysiological changes, it makes sense for an acute experience. Once it becomes chronic though, the narrowed field becomes “normal,” and attitudes like skepticism and cynicism become present, which I think are related to distrust, and doubt. Since stress is identified as fight/flight, the emotions are accordingly, as they appear in this illustration, opposite each other. The response usually calls for one or the other. I believe it was William James that said, “We don’t run because we fear, we fear because we run,” and I liked the attachment to the body, as well as the combination of the emotion to the flight. In my world of neurological states, that continuum then would be alarm, afraid, anxious, terror. Terror brings us close to the neurological state of freeze, depending on the level of helplessness. That would be the flight side. The fight side starts with annoyed, irritable, angry, enraged. In watching people defend themselves, rage is anything but precise or styled. I like the word apprehensive though. I’m going to play with that!

Here’s another place where I would differ: I’d put both of those emotions in the contraction phase. Physiologically that’s exactly what the body does in fight/flight. It contracts and tightens, what Thomas Hanna called the red light reflex. Returning to the neurological state of social engagement then is the green light reflex, where muscles are relaxed, the heart and breathing even and moderate, and the emotions one more of the expansive expression – even as well, and joyful, happy, content, serene, loving. Life is meant to pulsate, which is a constant contraction/expansion action. The body does it every heart beat. Those days that suck? That’s a contraction day? The two months that saw a loss of the SO, the vehicle, the job, the place to live and two friends dying? That’s contraction. Even in a state of social engagement, that’s contraction. And every contraction is followed by an expansion unless the new normal is a state of stuck contraction, and that’s pretty much what I call trauma.

Thanks Josh!

As I read this, Accomplishment, Belonging, Purpose and Safety are all the work on resilience too, both personal and professional. If we consider professional resilience the questions we ask to assess resilience are along the lines of: Do you feel part of the team (belonging)? feel you have the skill set to achieve (accomplishment)? Can make as difference, have self-efficacy (purpose)? and is your work environment /hours of working is in line with needs of home life (safety)?

Hey Joshua, first time commenting and so appreciate your insight and inspiration. I always learn a little bit more about me and see fresh ways to support my clients reading your articles. In our shop, we like to look at emotions through the lens of weightlifting and Judo. There are times when you are bench pressing that to lift heavier you need to “feel” the weight and be able to do that, knowing it won’t crush you because your spotter (coach) is taking the weight with you. Feeling the weight in terms of emotions is being truly curious without any expectations, judgement or opinions starting with yourself and exploring the “why” of the emotion. Essentially creating a safe but challenging space for growing through it which leads us to Judo. When we are confronted with emotion, ours or someone else’s, we have a choice to take its energy on or like the art of Judo move the energy to a desired location. When it’s a positive emotion we move to celebrating the wins; how has this emotion helped me inform who I am and why I matter. A negative emotion is about restating it not as a barrier, loss or fear but rather a cry for help and a learning day. I know this sounds very simplistic versus all that has been shared here but we find that it is often the simplest catalyst that creates momentum (relational capital) that starts moving a wall versus more acceleration (transactional capital) that becomes about how fast you are going to hit the wall; often again. Thanks again Joshua for your leadership!

Amazing inputs..wish i knew about these concepts while i was a child..also the yin yang symbol is mesmerizing.

What an amazing article! with very interesting and valuable comments. Thank you.

I read all the comments (took me couple days in the subway to read and digest). I have to say most people (with also many exceptions) sounded as if they are studying emotions outside of their bodies. Emotions sounded as if they are foreign objects to study and look and come up with ways to show them as shiny things…this is my attempt of being sarcastic.

I would like to add few points. First, I need to post a disclaimer. My disclaimer is I had a very turbulence and violent childhood but with the sheer force of something, I have a very happy, satisfying and functional life. I am also a student of psychotherapy as a second career. Now that I get that out of the way, I would like to add few comments to the discussion.

These are my opinions for today and subject to change as I grow and learn more.

Emotions are needs that did not meet (way back when before language was learned), or have not met today, or will not meet tomorrow. Emotions go through all tenses not only today or tomorrow.

Our personalities are based on emotions and things we were subjected to when young. Could be having a great childhood (though hard to say that exist…even a great parent will have a bad day that could happened at critical moment for a learning toddler); or could be opposite on the spectrum for a person like me. Nevertheless, all our personalities are based on quite a template that was created back then. It is extremely important to become aware of this template and how much it impacts emotions felt, learned, and reacted to as an adult today. Without acknowledging that, it is truly hard to discuss about emotions.

My biggest reaction was to why do we believe some emotions are unpleasant? Is it because they impact on the brain in negative manner? Why exactly anger is considered bad or unpleasant but happiness is considered good or pleasant?

I know few people who grew up in trauma invested homes or were in wars or in prisons (that I read), and they all seem to come to appreciate all the feelings they had then that made who they have become (Victor Frankl anyone?) So even emotions or feelings we consider bad/unpleasant have a very biological purpose just as important as happiness and joy…just as important. To biology, your happiness or anger does not make difference but for you it is lighter or heavier on your body! So is it the heaviness we do not like or the heaviness causing some neuron damage?

As many others already said in a much better than I could do ever articulate, all emotions are good. Even the bad ones have good reasons and feel good when we are telling a story of a time that feeling or emotion saved our lives. Imagine you kicked into high-gear of protection (fear) to save a child. Fear is not good (as per our conversation here) but fear is really good in that incident because it made you do a great thing to save a baby and not everybody would have the same reaction as fear. Some people may say, I want to keep my happiness and not get involved.

As I mentioned earlier, I grew up in a very hostile environment and yet I know the feeling of happiness, falling in love and living in loving environment but yet, my personality was developed while I felt “threatened” by my mother as a very young age (probably before language was learned). I must fell into a threat state. I had that “threatened” personality in most of my adulthood. Yet, I fell in love. I experienced moments of bliss. In order to make sense of my emotions growing up as a young adult, I narrated within myself that I am a protective person (because my brain wanted to choose a softer word to make me feel safe). I never actually voiced I was threatened even though obviously I did not protect myself from my mom when I was a toddler. All I could probably do was feel a threat and dissociate from my body (complete tonic immobility).

So as an adult, the question was (that I asked myself) what am I being protected from what? Because I felt the emotion of threat driving my insides. Then I learned, I was not protected (cause no child can be protected when abused) but I was threatened and stayed on that state forever, until I clicked.

The use of language helped me here. I am not protected person. I was threatened and got stuck on that threat and never really get off…until of course, I got in touch with myself during intense meditation where I listened to my feelings alone…shut the mind.

What did this teach me?

Emotions are like wave. They are all good even anger and fear are good feelings when you face a danger. Facing a danger and being happy is not good (so the good and bad emotions are things we create in order to use language). Waves wash over us as anyone knows who ever felt a strong emotion. Waves AKA emotions are what make us connect without touching anything and what makes us see things from distance as feeling. A lot of parents feel when their child is sick even if that child is an adult living in another country! That is a wave an emotion. It has no shape or space. They are not on continuum as also some others said. Emotions are like water or air. They have no shape or line or direction. I call them wave. Some of us can have a tsunami hitting on them and that can be overwhelming and some of us can have draught and just as the same. Even too much happiness, one does not get to be too motivated to go and save the children from a war. So the wave has to be certain balanced to wash us over not overwhelm us.

Maybe overwhelming or underwhelming is good way to describe an emotion.

Where I thought we lost a touch was the comparison with the rational thought or what to do when an emotion and rational meet. To me (again my belief today), a rational thought is a particle. We have rational thought so we could build things and plan and create things not to feel. We use rational at work more than emotion because we want a result. We want to see what we did. Rational is doing things and making things and creating things. Emotions are feeling (not good/bad unpleasant and pleasant) but things that make us feel an image in our head warm our body or make us cold and frigid.

All emotions are good. To have empathy of anger for a person feeling angry because of injustice is good feeling but it is still anger. Only it is not overwhelming us…so we an still function to do what we want to do. Emotion should not impair us. It should enhance our functioning.

Comparing and mixing emotion and rational mind is confusing.

So to me what is EQ then? It is knowing when the wave is washing over the particle part of me and I do not dissolve completely. No matter what the wave was about. I experience full wave without going along with it and still feel the particle part of me grounding me to the universe/earth/plane etc.

In other words, if extreme anger comes over me (from watching tv for example), I let it feel as a wave all over my particle (my body and mind) and let it go all the way to the ground. It may feel funny or weird but it is good/pleasant cause by observing the wave on the particle is not good or bad state at all.

If one gets angry and does not observe and let the wave take over, that is no longer an emotion but action and dangerous one depending on its severity and consequences.

Same thing can be said for happiness (everybody says it is fleeting thing right) but it is the same thing as anger. It is also a wave over the body and has to be felt fully without attaching anything to it, until it is gone to the ground or leaves by the head (whichever works for you).

I hope this makes sense. English is not my first language.

I thought I will just add my two cents. I loved this kind of stuff and every commenter sounded so smart and so articulate.

Thank you for enlightening me.

M

thanks

What a simple and beautiful principle: Emotions are neither good nor bad!

Growing up in a family and community that shunned emotional displays, talking about emotions and refused to see any good coming from ‘traditions’ like believing & religion, I can safely say that this is a revelation. I can see how I have been reproducing these patterns in my own life and how I especially turned them on myself. I recently lost my dearly beloved father and I find myself still apologizing for those moments when grief floods through me. Many of our Western cultural norms lie deep under the surface of how we raise and teach our children.

On the other hand I witness soo many unrestrained emotional displays on reality TV and social media, I makes me wonder about the future. Lashing out in anger or digust seems to become the norm in certain circles and age groups. Why do we seem to swing from one extreme to the other extreme? I just realised I need to navigate my son with his set of emotions through this murky water of the future. Thank you for offering light and for doing continous reseach. It feel so much more empowered but also challenged.

I liked the thought that each feeling is a part of a bigger story – looking at why we feel the way we do might give bigger understanding to the story in stead of the feeling itself.

If a person feels he is disturbed/ mocked / made fun of by others, he will naturally learn to ignore those taunts, perceived or otherwise in due time. He would have heard all the meanest and cruellest remarks not once, but a few times over by the time he gets old. Thus, hurtful words will lose the intended sting ultimately and fail to stop him from going on in life. This is only fair.

Hi Jess – that is one possible outcome. Another is the person “naturally” internalizes those messages, comes to see himself as “something less.” You might want to google for “internalized oppression”… I wish life were more fair, unfortunately, sometimes it’s not.

Joshua, thank you, I really liked the article, it was useful for reflection and growth.

I share some thoughts on some points, emphasizing the Christian perspective, the way I learned (there are others):

Today, in a world that is not perfect (yet because I believe in the restoration), really need all emotions (however after restoring, sadness will be not necessary). I undertand that we feel all emotions and that we have to know and think about all emotions and act on them (we can not just ignore them or judge them: right or wrong). We must mention however, that we must also reflect on what emotion is right for each situation (we can not ignore this aspect): to betray (tamper) a person, is not an emotion of joy (I believe that sometimes it happens because the man still has a tendency to error). Feel joy at this situation, it is not correct, however, in this world (which is not perfect yet) this emotion can be useful to prove that this guy has other things like: selfish. In the Christian perspective (I learned and believed) he must regret, and in this situation I believe that one of the flows (among others) that would be occurring: think, act and feel later.

However the flow above presents a possibility of the following scheme: think (from the perspective of Jesus), act (without full understanding), feel (if the person align his emotions) and internalize this understanding (if the person change his mind).

I believe that in many situations this process stems from the faith.

Thanks a lot.

Bruno

You have the same name as Bruno Mars, the popular South American singer who sang ” You make me feel like I am shut out of heaven…” I thought those choice of lyrics were highly risky.

Thanks for sharing Bruno. One of my Christian colleagues shared this perspective with me: “We are made in the image of God, and that includes our emotions. We have them for a reason.” So rather than rejecting this gift, our job is to figure out how to use it well.

This a great article.. I’ve enjoyed looking a little deeper at my own emotions in the past few days… why am I feeling what I’m feeling? What’s behind the emotion? What’s it telling me about me and about what I’m doing/ thinking/ seeking? Rather than reacting I’ve found myself reflecting.. It’s quite a ride when you start digging behind the signals – get to know yourself better through those emotional moments!.. And now apply that to those around you!!

Also, I particularly liked the idea of not being able to have anger without committment… Think of that guy in your office who gets really angry about the way your company/ organisation/ team operates… Is he the one who also puts in the most hours (or at least would if asked)? He’s not the first person you would call out as a “model” corporate citizen/ team member yet he’s the one who is first in the queue with the bucket of water when the fire starts raging… Maybe it’s just me but I’ve seen these kind of folks a lot in the corporations I have worked for.. I’m thinking their anger may give away their “committment to the cause”…. So is the challenge for leaders to better understand and harness this anger/ committment in a positive way??

Hi Spencer – it’s an interesting point: What if we saw strong emotion as a signal of strong commitment… even if that emotion is “negative” maybe it’s only present because of something “positive”? And, if we move away from the judgment of +/-, and instead just look at valence, we see there’s a lot of energy in these people & situations, and we need to harness the energy!

Hi Spencer – I agree – the challenge is for leaders to see and use this energy — the first step is to see it’s a resource. At work (and with our kids) we often see “negative” emotion as a sign of something negative (“he’s angry so he’s not a team player.” “My kid is having a tantrum so I’m a bad parent”). If we let go of that judgment, it’s easy to reframe: Apathy is the enemy of growth, all emotion is a signal of engagement.

Respected Joshua Freedman,

I value your contributions In EQ teaching and glad to read this article. Presently I am doing certification program in ICA and working on my thesis on EQ awareness . I request your permission to quote from your articles as it is stated.

With warm regards

V S KUMAR

Thank you for asking Mr. Kumar – I would be very pleased to have you do so.

– Josh

Joshua Freedman,

Sir,

Greetings.Honoured with your prompt reply and permission. In fact I am keen in getting certified by 6seconds on EQ. Presently I am a Student of ICA. I find the fee structure is beyond my reach at present. If there are scholorship facility & other possibilities of paying it in parts, I am really willing to attend theCertification at Mumbai. I have a passion for understanding EQ and support in my Journey as a coach.

Sir, I welcome you to India.

With gratitude,

V S KUMAR

ReCreate Life. May I Assist You?

Dear Mr Joshua, Your articles on emotional intelligence are useful and educative.You are doing a world of good to the readers across the globe.

yours sincerely,

JVL NARASIMHA RAO

INDIA

Thank you Narasimha – comments like this help me want to continue! I’ve just arrived in Mumbai a few hours ago ready for an exciting 10 days of transformational EQ teaching. 🙂

As you might have predicted, I continued to have thoughts about this subject after my lengthy post. First, in addition to “pre-rational”, “sub-rational” and “supra-rational” might be used to describe the link between emotions and rational thought. Do any of these make more sense that the others? Also, I thought a summary of how I perceive the model might be helpful. So, here it goes.

An unpleasant emotion is an indication that some need is not being met or is in danger of not being met in the future, while pleasant emotions are indicators that needs are being met, or are very likely to be met in the very near future. Mixed emotions might indicate some ambivalence or confusion as to whether or not one’s needs are being met. “Needs”, as used here, will also include “wants” (not critical for survival).

Once you’ve experienced the emotion, appreciate the emotion and express gratitude to the emotion for alerting you to whatever has changed with respect to satisfaction or your needs. Find out what thought, action, and/or situation has changed, and that is prompting the emotion. The type of emotion (pleasant or unpleasant) will help you determine whether to look for needs that are not being satisfied, or whether to look for needs that are being satisfied.

If the emotion was unpleasant, determine whether non-satisfaction has to do with a want, or with something that is needed. The concept of non-attachment may come in handy here. If it has to do with a want, consider how reasonable the want may be. If it has to do with a need, adjust your activities (if possible) to maintain satisfaction of the need. Consider whether the emotion is accurate. Is the need really in danger of being unfulfilled? If not, adjust your thoughts.

If the emotion was pleasant, determine whether the satisfaction has to do with a want, or with something that is needed. Express gratitude and appreciate the change in need/want satisfaction accordingly. Either way, savor the experience and the satisfaction of the need.

As a person’s empathy and compassion advance, the needs considered will extend beyond one’s own personal needs to include the needs of all persons. Perhaps, if the person is on the path to true enlightenment, this perception may extend to all sentient beings, and then everything, and then to nothing at all.

Greetings to my friends Josh, Robyn, Sushma, Neri, Julie D., Lisa, Kristy, Melissa, Mervyn, Anthony, Charles, Angie, Laura, Alice, Allen, Sandeep, Parag, Kari, Morgan, Lorraine, Cherub, Rosiemerry, Julie B., Uday, and the rest of the Six Seconds family!

It seems that much of the puzzle around these issues has to do with our adaptation of our language and misuse or misappropriation of our words. And then, as Josh commented, we often reinforce that inaccurate or unintentional meaning for ourselves and others. This may be what we’ve done with many of the words used in this discussion.

As Sushma points out, “good” and “bad” are judgmental. That’s because they are ethical (moral) terms used for expressing our judgments with regard to behavior. I suspect that use of these terms was much more limited long ago, but misappropriation and over-usage has made them the most generally used evaluative and descriptive terms to commend and condemn not only behavior but most everything else we know. Many people use the terms without any intention of making a moral statement. When a person talks about eating a good banana, it is unlikely she’s trying to indicate that the banana has some moral goodness. Yet, to say the banana is “good” still has some connotation of moral goodness. A person is more likely to gain some type of benefit from eating a good banana, and more likely to not benefit (or even suffer) from eating a bad banana.

Since, in the moral sense, all emotions are “good”, there’s little to be lost by avoiding the words “good” and “bad” with reference to emotions. It would be like abandoning the use of the words “round” and “triangular” when discussing bowling balls. Because few, if any, bowling balls are triangular (or any other shape other than round and spherical), it’s pointless to differentiate or characterize bowling balls in this way.

The only emotions that could conceivably be termed “bad” would be those that are inappropriate for the event triggering the emotion. It is “bad” to feel glee when torturing puppies. But then, it’s not so much that the emotion is bad, but that the misappropriation of the emotion is bad. We use the words pathological and seriously mentally ill for people that frequently fall victim to inappropriate emotion. Sometimes, we even go so far as to call such persons evil.

Laura’s word “irrational” may be more appropriate for these cases. Yet, emotions are not supposed to be rational. So, to say an emotion is “irrational” may make no sense at all (since it should never be rational). A parallel might be my calling a coffee cup irresponsible. Since I never expect a coffee cup to be responsible, saying it is irresponsible doesn’t say much. To be effective, emotions must be “pre-rational”. In short, giving up “rational” and “irrational” with respect to emotions should be easier than giving up “good” and “bad”, and no different than our giving up the terms “triangular” and “oblong” when we talk about bowling balls.

The exception, where the use of the word “irrational” might be appropriate, would be those emotions that are too extreme (either in intensity or duration) for the situation. But it only takes a little contemplation to recognize that this is just a variation of the misappropriation of emotion discussed above. So, again, it is not the emotion that is irrational, but the misappropriation. This seems to be what Neri is alluding to. Once you’ve cognized whatever it was the emotion was meant to convey, there is not a rational need to continue feeling the emotion. A person could irrationally conjure up thoughts or engage in activities that trigger various emotions. These might somewhat accurately be called “irrational” emotions, even though it is not the emotions themselves that are irrational. These may be the emotions to which Laura is referring. Navigating emotions, applying consequential thinking, and practicing optimism (and other rational thought/action) are good antidotes for these emotions.

I think the use of the terms “positive” and “negative” is another misappropriation – this time of mathematical terms. Perhaps the usage is an effort to shirk the moral judgment required when using “good” and “bad”. But, since emotions are not in any way mathematical, the terms are not descriptive in a mathematical sense. Perhaps the purpose for “positive” is to connote some type of gain, while “negative” is to connote some type of loss. If so, the terms hint at some truth, since we often have “positive” emotions when we gain something we need, and often have “negative” emotions when we lose something we need. However, the terms are not all that helpful.

While I support giving up the use of the terms discussed above when characterizing or describing emotions, I think it would be extremely unwise, and downright foolish, to abandon the use of “pleasant” and “unpleasant” with respect to emotions. It is the very unpleasantness of fear, guilt, anxiety, anger and other similar emotions that make them so very essential. It is their unpleasantness that gives them value and makes them “good”. Just as physical pain (which we’re learning is processed by the brain in the same way as emotional pain) is useful precisely because it is unpleasant, so is emotional pain. If fear were not unpleasant, we’d certainly find ourselves in many more life-threatening situations.

Likewise, it is the pleasantness of joy, ecstasy, satisfaction, and contentment that makes them valuable as emotions and as states of existence. If we gained no pleasure from these, if they were unpleasant, we would have no interest in or desire to experience them. (Though, we should keep in mind that sometimes we can get a limited amount of pleasure from generally unpleasant emotions. Josh mentioned that sometimes it feels good to feel angry. Even so, anger does affect one’s brain chemistry in not so healthful ways. And, I can assure you, that the anger is unpleasant to someone, even if not totally recognized as unpleasant by the angry person.)

I believe we can embrace these seemingly opposite classifications of emotions (pleasant and unpleasant) without “giving in” to rigid dualism or assuming that specific emotions have polar opposites. Like emotions, the classifications can be different from each other without being opposites. A continuum or spectrum is a helpful visual. However, while it’s not strictly dualistic, it is still linear. I don’t believe pleasant or unpleasant (or much of anything) can be accurately thought of in this way.

It seems to me that most of those emphasizing the non-dualistic nature of Buddhism are Westerners talking about Buddhism; while my (admittedly limited) reading of Buddhist literature shows the literature to be replete with dualistic language and comparisons. Frequently occurring themes include the juxtaposition of good and evil, love and hatred, compassion and selfishness, attachment and non-attachment, peace and violence, suffering and happiness, and ignorance with knowledge, wisdom, and enlightenment. Perhaps it is not the dualistic language that we should avoid. Perhaps it is dualistic thought that is to be avoided. So, while there are frequent dualistic comparisons, Buddhist literature also continually emphasizes (sometimes within the same sentence as a limiting dualism) inter-connectedness, interdependence, inter-being, limitlessness, impermanence, and inclusiveness. The person on the path to Buddha enlightenment will be keenly aware and mindful that the dualistic language is merely a tool to facilitate communication and not a true or complete reflection of reality.

Getting back to emotions, Shapiro seems to hit truth by recognizing emotion as an indication of need. Once we can determine the basic need driving the emotion, we can then, as Allen suggests, use the emotional information in ways that improve our quality of life. Or, as Josh put it, we can leverage emotional data to achieve our purpose. But then, emotions can be tricky. We might be wise to do as Melissa suggests and “determine whether an emotion is aiding or hindering the achievement of a need”. If an emotion were hindering the attainment of something truly needed (or what we really want), it would be irrational to continue harboring the emotion (at least in that situation). Either way, we’ll want to remember that emotions are always telling us something, always working for us (unless we happen to fall into that class of pathological or seriously mentally ill). How could they not? They are us.

Finally, I’d be neglecting my noble goal if I didn’t comment on the idea of happiness. Happiness is seen as the ideal because it is the ideal (as far as we know). The needs listed by Josh – accomplishment, safety, belonging, and purpose – are either conditions of and/or means to happiness. If any of these did not somehow contribute to our gaining happiness, we would neither need nor want these. (By the way, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs would also work for building the model.)

Please keep in mind that I’m not talking about a fleeting emotion called happiness – the type of thing you experience when eating your favorite ice cream on a hot day. (My suspicion is that the term “happiness” has suffered the same type of abuse as have “good” and “bad”.) The happiness I am considering is a continuous and abiding state of joy which includes contentment, peace, tranquility, and even bliss with ecstasy. It is much more than an emotion. As valuable as emotions are, an emotion will never be a sufficient goal or purpose for life. Yet, the happiness of which I write is the goal of all people (explicitly or implicitly), and I believe it to be the primary, if not sole, purpose and meaning of life. That happiness is pleasurable and a means to yet more happiness makes a full explanation of this belief impracticable here. Besides, don’t you think I’ve said enough already? Suffice it to say, I think there is ample evidence provided by Eastern and Western philosophers, most (if not all) religions, and the burgeoning field of positive psychology to support the contention.

Thank you for a richly rewarding discussion. This non-dualistic, need-based model will certainly benefit a great many as it emerges and evolves.

Hi. I facilitate EQ/SQ workshops for management executives where I speak about all emotions as ok without necessarily being positive or negative. The expression of anger or fear etc can be negative or positive, or their triggering beliefs may be out of place, but emotions as such are energy that needs to be managed through awareness, understanding, and appropriate expression.

My notes on EQ are part of my notes entitled who is the captain of your boat. Sending you a link to the same

http://www.scribd.com/doc/18752567/Who-is-the-Captain-of-Your-Boat

I really enjoyed and benefited from this article Josh. I swear you must be reading my mind because the last few weeks you have chosen topics that are very timely for the work I am doing. Thank you so much for bringing Marshall Rosenberg’s Nonviolent Communication into the conversation. I was introduced to his teachings several years ago and just recently came back to them while creating a workshop on conflict resolution. There is such a strong connection between emotional intelligence and his philosophy, and it caused me to go back and dig deeper into how to teach others about emotional literacy and the value of feelings. In my attempt to move away from judging/labeling feelings as good or bad, I chose to use “pleasant/unpleasant” as a compromise, but it never felt quite right. Your article was able to help me realize what wasn’t feeling “right”. Don’t you just love “a-ha” moments? That’s what Six Seconds is all about!

Thank you, Josh, for sharing your gleaned insights. The beauty of our feelings is that we all have them and how we respond to them is our individual and collective growth to their oneness of purpose.

Your analysis serves as an affirmation for me. The feeling arises; it is recognized; its source is identified; a response is chosen with the intent of bringing about harmony for self, others, and situations; the process results in an awareness of COMPASSION;

Thank you! This is very interesting and useful. I am sure if I work through it, it will help me get “unstuck” from the paralyzing effect of emotions I have hitherto perceived as negative.

Great Cherub – let us know what happens!

My Director of Organizational Development directed me to this article. I particularly found it interesting that you chose Buddhism as a lens with which to view what is a symbiosis rather than dichotomy. I’m very interested in exploring the connections between positive psychology and Zen so your venture in a similar direction certainly helped draw me in. I think you make an excellent point.

My main question for you however is regarding anger. Do you consider it an obstacle when someone insults you and you get angry? What path are they blocking? And to what degree is the anger the fault of the person insulting you and to what degree a reaction that we should own. (As in those who say, “I didn’t make you angry, you let yourself get angry at me.”)

Hi Morgan – I appreciate both your questions about anger. I don’t know.

My first response is:

— If someone insults me, I feel angry because there is something I want (someplace I want to go, not literally, but in terms of relationship). I spoke to someone yesterday who I found to be subtly and consistently insulting to me — if I genuinely didn’t care, it wouldn’t have mattered to me. However, I wanted something, I wanted to move the conversation in a particular direction… and this was definitely an obstacle for me to navigate… and in this case, I chose to put the anger aside and consider it later to become clear what it was that I was really feeling. Maybe a combination of fear, hurt, and disgust — which was bubbling together with the anger.

— People are social beings. We are wired to connect. So, it’s not “optional” that we respond emotionally to one another. It’s immediate and visceral. So, I’d say

a) setup — we’re in a state, which we’ve chosen. Maybe calm and collected, maybe frazzled.

b) trigger — someone says something

c) interpretation — we begin to react — automatically, and also we start to make meaning of it.

d) reaction — we continue to define the meaning, and this shapes how the reaction unfolds.

e) escalation (or not) — we keep processing the data, and either we continue to “go up the ladder” or choose to get off.

This point is now part of the next time around the cycle. We call this the Reaction Cycle and we have a tool called the Reaction Roadmap — I hope to write more about it soon.

If this perspective is interesting, have a look at this article that I wrote for children about this: http://staging.6seconds.org/2010/09/15/smarter-about-feelings/ — check out the little section called “Emotions as Messages”

Warmly,

– Josh

A very interesting and thoughtful article Josh and fascinating replies – thank you.

As part of my work with individual clients and organisations I readily use the concept of EI. It also plays a part in my life in a broader social sense – through the civic and voluntary organisations I belong to. and the issues they address. I am interested in it’s place in the education system too – so too much to say, and too many questions for this reply!

So just a few comments and questions.

How would you place ‘rage’ or ‘outrage’ as opposed to anger in your schema Josh?

In answer to one of the replies – when ‘talking’ about emotional intelligence is not working, (eg: a manager has an anger issue, understands the concepts of emotional intelligence but fails to apply them in the workplace) I have found that trance work and ‘time line’ work (going to earlier states, often childhood, where the emotion is present and then forward to the adult state to inform the past with the present maturity and visa versa) can be effective. Visualisations in trance can also help – visualised role playing or visual or spoken metaphors.

I am interested in how emotions work in larger groups or populations and how much is influenced by a group past history and events? What role do ‘expectations’ play in the emotional response of a group? What is instinctive and what is learnt? (One of the respondents talks about how they were taught to exert ‘self control’ for example, an expectation of behaviour was imposed upon the emotion). What is the possible range of connections between emotion and behaviour?

Most humans are very good at identifying emotional responses in others, before any words are uttered. We then often use ‘words’ to react to or negotiate our way through that response, at which point what we say and how we say it becomes important. It is not just our own emotions that we need to be aware of and thoughtful about but how we process and then react to the emotions of other people.

I think your comments on parents and children are pertinent Josh and all of us parents could benefit from some ‘parenting’ seminars from time to time.

I know of someone who has developed an excellent programme around the concepts of EI with children, how to recognise and use the emotions one feels as a parent as a means to helping the child develop. One example she gives is if your (older) child tells you they are going backpacking around Thailand and your reaction is immediately one of fear and anguish, rather than saying ‘no you are not, it is too dangerous’ to be able to recognise that it is natural to want to keep one’s child safe, but also natural to want them to grow and experience life in order to arm them against dangers in the future, so keeping them safe.

One can discuss ways to mitigate the dangerous aspects of the enterprise without having to veto the entire project. In other words one can respect the emotional response one has as a parent but recognise it as a signal that one is at a border of development for the child, one which they may need help navigating their way along.

Lorraine

Thanks Lorraine, intriguing points. “Rage” is probably a feeling that combines anger with some other things, including a judgment that “I’m right and you’re wrong” and probably fear as well — it focuses our attention on the enemy and motivates us to destroy. It’s still tied to a need to accomplish, and a decision that the only way to accomplish what we want is to destroy the other. Which is unlikely to be the objective truth, but sometimes it feels that way!

In your penultimate paragraph you talk about the teen who wants to go to Thailand — I’d just add that this is a beautiful example of how we actually have MULTIPLE and often paradoxical feelings at the very same time. In the article I talk about fear only existing because of the caring that we have for the child. We can be proud and excited about their maturity at the very same moment that we’re wishing we could hold them tight.

If we get angry because someone insults us it could be our craving for acceptance (belonging) or our low self-esteem (feeling of rejection). I believe in saying that for people to insult us they need our consensus and it equally applies to provoking anger.

Thanks Joshua!

This actually came at perfect timing. I am writing a lesson plan for high school students about worker safety and I’m teaching them skills in emotional intelligence. This relates perfectly well to how I am trying to teach them to become emotionally literate of the feeling of fear to help them recognize hazards at the workplace and learn how to effectively deal with them. Your idea of approaching all feelings as neither good nor bad, but simply beneficial to understanding ourselves is exactly the piece I needed to add in. I was having a hard time describing how emotions are important to us to provide an understanding of ourselves without much reasoning and how intuition can be a great thing if we focused on it more.

I am so happy for you work and effort into EI.

Sincerely,

Kari

Thanks Karl! I am so glad you found a use so quickly, and such an important use. If you haven’t seen it, here’s an article from one of our network members about EQ in industrial safety: http://staging.6seconds.org/2009/01/10/taking-industrial-safety-to-the-next-level/

wonderful article and whole new perspective. Is it possible to make a table of five columns need – want – emotion – situation – Best possible response. I know I am trying to simplify it but without this kind of ready to use tool, it will be very difficult for a common man to benefit from this knowledge base.

What a powerful idea Parag. I think it is over-simplifying, but we could say “this is an example” (not “this is the complete story”) — and this becomes an exercise for all of us. At Six Seconds, our approach would normally be to add very important ? mark to the end:

need – want – emotion – situation – best possible response?

I do think it’s useful to offer examples and stories — AND it’s essential that we encourage people to find their solutions… because the truth is that my solutions “sort of work” for me, they’re unlikely to work for everyone.

🙂

This is incredible stuff !! Written with somuch of clarity.Thank you so much Josh for this one.I liked the way you explained emotions as Focus and Motivation perspectives and also about anger-commitment nonduality.This inspiring article with deeper understanding, will guide all of us to reach out to others with even more clarity.This in turn will help many to reach out to the “Ecosystem’ (the 85% of our iceberg) of our body-mind,which is absolute necessity for effective and optimal performance,

I appreciate that Sandeep. Let’s make it so!

Really long post, read at your own risk, and do not operate heavy equipment while doing so. 🙂

Your article makes a lot of sense, and as a proponent of NVC and their articulation of needs and how needs impact our lives and conversations, the direction of your article resonates with me. Emotions as a continuum…..paying attention to what our emotions are signaling for us…..decoding, and so forth all are in the arena for better self understanding and building emotional intelligence within.

At the same time, practically speaking, our discussions are cognitive, and as such when we meet with and discuss with others to educate and “enroll”, the cognitive approach alone may not be enough. I sense that when you tell your own stories you are working to include the emotional foundation for these discussions. A useful approach—and perhaps still not quite enough to make breakthroughs. (I’m not saying that we shouldn’t take this approach, it is very effective and I’ve used it to make things more human, more real.)

Certainly, the learning methodology that Six Seconds models is another piece of the puzzle toward educating, “enrolling”, and helping others make their own breakthroughs. And maybe there’s more…

I have been working for the past six months with the majority of our leaders (managers and supervisors) using Six Seconds DHP Leadership modules. This has been an enlightening experience. Not only have I become more adept at the learning methodology, I have noticed the incremental changes that have happened with the folks, each at their own pace, and some not much at all. To expect dramatic transformation in a short period of time isn’t realistic in our environment where many of these folks have been imbedded in a very specific culture for years (15 – 30 years plus). Still, I am encouraged.

Consider this then. If these folks move slowly toward greater effectiveness and greater emotional intelligence in this culture, imagine the magnitude of the task with the human experience of working with adults many of whom have grown up with familial, social and cultural influences for the majority of the totality of their life experience. A mouthful, but you get the drift, hopefully.

And today, we are in the “speed”/overload zone. Get your message out their quickly or you lose me—the less than 30 seconds Elevator Speech. By the way, I don’t really think we are really living EQ if try to reduce it to that, yet that’s the challenge.

What I’ve also noticed in working with leaders in our organization with the modules, is that they seem to “get it” and really want to apply their insights and new tools—but have difficulty doing so. And, I don’t think it’s a skill set, practice issue. It feels like it’s more of the emotional barriers and patterns that became inculcated over their breadth of life experience. The Synapse School is starting at an early age with children so that more effective patterns and relationships with emotions are cultivated. What now for adults?

All of the above moves us in a productive direction, but is there something else that needs to be added in, some deeper (without being psychoanalytic) way of helping folks make the breakthroughs?

Perhaps Josh and some of the other Six Seconds and EQ learners who have been at it for a while, might be able to look at their own journey and what were the breakthrough moments they experience, and what seemed to trigger or at least be helpful in that happening. Maybe there are some clues there. And sharing that with this network might help us all be more effective in helping others (and ourselves as it seems to be a life journey).

Here’s one thought (without much thought…more intuitive):

Share a personal insight from when you were a child. For example, “I used to get so mad, or cry when kids would call me names and tease me. My mother would try to help by saying ‘Sticks and stones may break my bones but names will never hurt me.’ But it did hurt. I had a very loving mother, and sometimes when she tried to help, it made it worse. Like when I was petrified of the water, when everyone else in my family was a swimmer, and she said, ‘You don’t need to be afraid, everyone can float and learn to swim. It’s fun.’ Not so much.”

Then ask a question. “Anyone else have something like that when they were a kid?”

Ask, “How did it feel?”

Ask, “And what did you do then?”

Ask, “Would you like to have done something different—what would have helped?”

Show appreciation for their sharing.

Share an adult experience involving emotions, and how it impacted what you did. Then relate it back to what you learned as a child without giving any solution of how you are much wiser and made better choices now. If you did make a better choice, save that revelation for later in the conversation. Your goal here is to invite the other person(s) into sharing in a safe place.

Invite them in by asking the question, “Does anyone here have something like this that happened recently?”

Ask, “How did it feel?”

Ask, “And what did you do then?”

Ask, “Would you like to have done something different—what would have helped?”

Show appreciation for their sharing.

Now you have a real connection to emotions and how they impact each of us. Then you can seque with a statement that introduces Emotional Intelligence in whatever fashion you might want to. For me, it might look like: “So in these situations, either as a child, or right now, as adults, emotions are to some degree or another, always present. When it works for us (refer back to a “good” story someone told), emotions are working for us. When it doesn’t work out so well, emotions are not working for us. Emotional Intelligence is about including emotional information in our lives in ways that improve the quality of our lives, and our effectiveness with others. We make better choices.”

All of the above is stream of consciousness stuff and perhaps not very good, but it suggests a direction that might make the topic more real and accessible.

Just for sake of argument, whether you do something like this or some approach that you have found works, the next challenge is to help people to be conscious of the difference between talking and sharing about EQ, and applying it after they leave. In the DHP modules, there is always an Action Plan and Reflection component. For people who embrace that and follow through, I have no doubt that this is very effective. The question I grapple with is “So what gets in the way of feeling comfortable with sharing and role playing in the session, yet not wanting to look at a real life application that faces them after they leave.

I’ll end with an example of this. I’m not looking for solutions, I have my own thoughts and avenues, but I want to illustrate with a real situation. Here it is.

Woven through the DHP modules is the Six Seconds Model. We have had incredibly useful and insightful exercises, experiences and insights on trust, empathy, motivation, and more….

I recently met with two large employee groups to do a post review of a major organizational change. In a word, they were very distressed. Lots of issues. The headline is: “Our management doesn’t listen and doesn’t care.” When asked if they wanted their management to know of their issues, they had two concerns: “Will we be retaliated against?,”and “Will it even make a difference?”

Our group of leaders, who in our sessions has not only grasped the power of emotions, but who also has expressed their own emotions, stress, frustrations, etc., and who has also identified their best practices in building trust, managing change, etc. is very reluctant to do the one thing that the group most wants: to listen and show you care.

Clearly, there are some barriers to “taking this on the road” and applying it to a very real situation. They would rather hope that it “dies down, and goes away.”

I do have thoughts on this, and we’re going to deal with it, but I do think that this illustrates the depth of emotional patterns and barriers…and needs that present challenges in our work.

More than enough said………

Worth the read Allen, thanks for sharing this. I’d like to respond to 3 elements briefly:

1) Change is easy, but it’s hard because there is so much of it to do. As you wrote, there are just so many threads in the fabric of “the way things are.”

2) This is why the approach you’re taking with the Developing Human Performance curriculum is so important — rather than a workshop, you’re creating a learning process — as you wrote, over these last months you’re starting to see this sinking in!

3) I appreciate the sequence of questions you’re articulating. I see this as very “Self-Science-like” in the way we encourage people to draw from their own experience, notice the choices they’ve made and why — and then consider if they might have other options that would move them toward their real goals?

Keep rocking the boat, my friend.

typo: you wrote “contact”, im sure you meant “contract”…

“When we feel Disgust-Trust, it means the social contract that produces order is vulnerable (this contact can be within ourselves, and when we violate our own precepts we feel disgust turned inward). While fear also signals risk, it’s not usually tied to the contract but to the human implication. And it’s trust that signals safety; so perhaps the specific surety of trust balances with a specific peril of disgust, in which case this construct is tied to the basic need of safety.”

Oh dear. Thanks Alice, will fix it now.

🙂

Josh,

I continue to be inspired by your dedication to EI. It IS really tough to work with our emotions and very hard to teach this material. In my own life, I’m struck by the need to “endure” emotions that seem irrational until the “move through me.”

Hi Laura – maybe it would be helpful to reframe this – rather than “endure” could it be “observe”?

🙂

What’s a beautiful written piece – to challenge us to go deeper into our emotions – understand the duality of emotions and how it ties to needs.

Josh, as always, appreciate your depth of insights.

Angie Wong

Hi Josh,

This is an excellent piece of writing. I think it may be the best I have seen for talking about a very difficult concept, i.e., identifying all emotions as valuable rather than positive or negative. For me, there is one part that does not work and that is the last section tying emotion to needs. It is confusing in part because you include Plutchik’s model and than offer anger commitment and fear love as items from someone else’s model. More importantly though I think you already have a helpful way of thinking about emotion by introducing your earlier chart that deals with motivation for emotions. Instead of introducing Shapiro and needs consider building on your ideas of motivation behind emotions. Overall very well done and if you don’t mind I would like to use your article in my work when the occasion arises. By the way you may consider using the word valuable in holistically describing all emotions. That is what I have been doing when I address the idea that people want to do away with negative emotions.

Warm regards,

Chuck

Thanks Chuck – I like Plutchik’s “pairs” too, and my sense is that they’re still in the concept of “opposites” — not single entities. So on his model where fear and anger are on one continuum, they’re both tied to a problem, which is why I’m moving away from that.

I’d be honored to have you share the article when it’s valuable.

Warmly,

– Josh